When we were kids, we drove all over the place. Mom and Dad had to drive a lot, because we lived in The Middle of Nowhere Rockbridge County Virginia. Mom drove a station wagon, which was small and green with a motor that always sounded wimpy and disinterested, yet taxed to the limits of its manufacture. It also smelled perpetually like French fries, which was not really the wagon's fault. That was mostly the fault of four children who rode around in the back shoving each other and trying to figure out how much fast food would fit into the upholstery gaps.

Mom's station wagon had a big cargo deck in the back, where on trips during the week we'd sit and build Lego sets, or curl up with books, or drum our feet on the floor and roll around, because it was the late 80s and early 90s and car crashes hadn't been invented yet. Sometimes there were bags of horse feed back there, which I once made the ride home sitting on top of, mostly in defiance of my mom for telling me to get down. It was pretty uncomfortable.

Every Friday night, we'd stay up and wait for Dad to come home. You'd hear him long before he arrived, and before you heard it, you'd feel it. This was nothing supernatural! It was just the sound of Big Red.

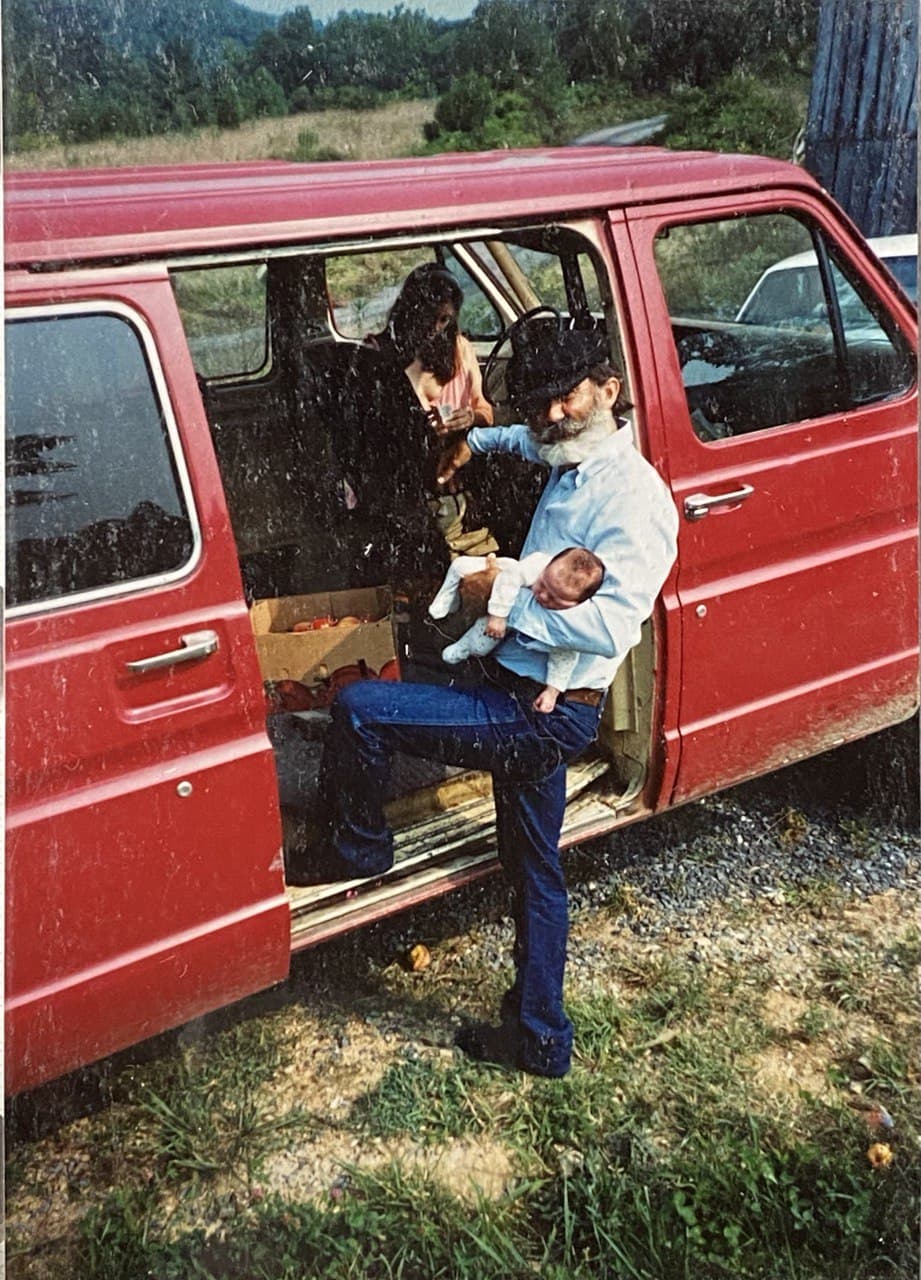

Big Red was a 1983 Ford Econoline, painted bright red but with a tan interior. Dad had wired a pair of mysterious plastic toggle switches into the dash beside the radio, the purpose of which was clear to him – and only him. The van had two bucket seats up front, a wooden cupholder installed on the dash, and two full rows of bench seats accessible from the giant sliding door. Behind the rear bench seat was enough space for a couple kids to stretch out and sleep on the floor, nestled between Dad's toolboxes. With one of the bench seats removed, you could haul a stack of plywood sheets and some cinderblocks in back, with room for four kids to sit on the remaining bench seat with Cokes in one hand and a pack of sandwich crackers in the other. When you're around for two days every week and the house is twelve miles from town, you have to make every trip count.

It took a sizable heart to move those five thousand pounds of steel. A six-liter carbureted engine ("I can't work on a car with a damn computer in it," Dad would complain) turned the wheels through a three-speed automatic transmission. Deep and thrumming with a smoothly growling cadence that rose pitch lazily with the incline of the road, you'd feel the motor in your chest as much as hear it. Saturday mornings we'd jump out of our beds, yelling for Dad as we ran to the master bedroom. Usually he'd already be awake sipping coffee with Mom, and us kids would clamber all over each other to be first to tell Dad about the events of the week while pilfering the Little Debbie cakes from his suitcase.

We'd try not to ask right away, but Dad knew what we wanted: a ride to Lexington in the Big Red Van, to spend allowance and maybe get breakfast in town if the stars aligned. Whatever the errand, we took the van whenever possible. With gas around a buck fifteen per gallon, who cared about the five extra emm-pee-gees the station wagon got? Like safety, nobody had thought to check on the environment or climate change yet. We'd throw the week's laundry in the back and drive out to the laundromat, usually one in Lexington, or later on the nice new place that opened on the hill overlooking Interstate 81 in Fairfield. Afterward we'd cruise through the backroads to Goshen, the steamy scent of fresh laundry mingling with petrochemical smells from Big Red and Dad's heavy mechanic's blanket folded in the space between the toolbox and the wheel-well. We'd grab a soda and a pack of crackers and eat them parked overlooking the Maury river, the van's big sliding door open, our butts on the step and our legs dangling above the asphalt.

Man, there might never have been a better vehicle. Try and have a childhood like that in a RAV4. Of course, not being glued to our phones for every minute of our drive was a help.

Comments